She's Lost Control

An essay on CONTROL

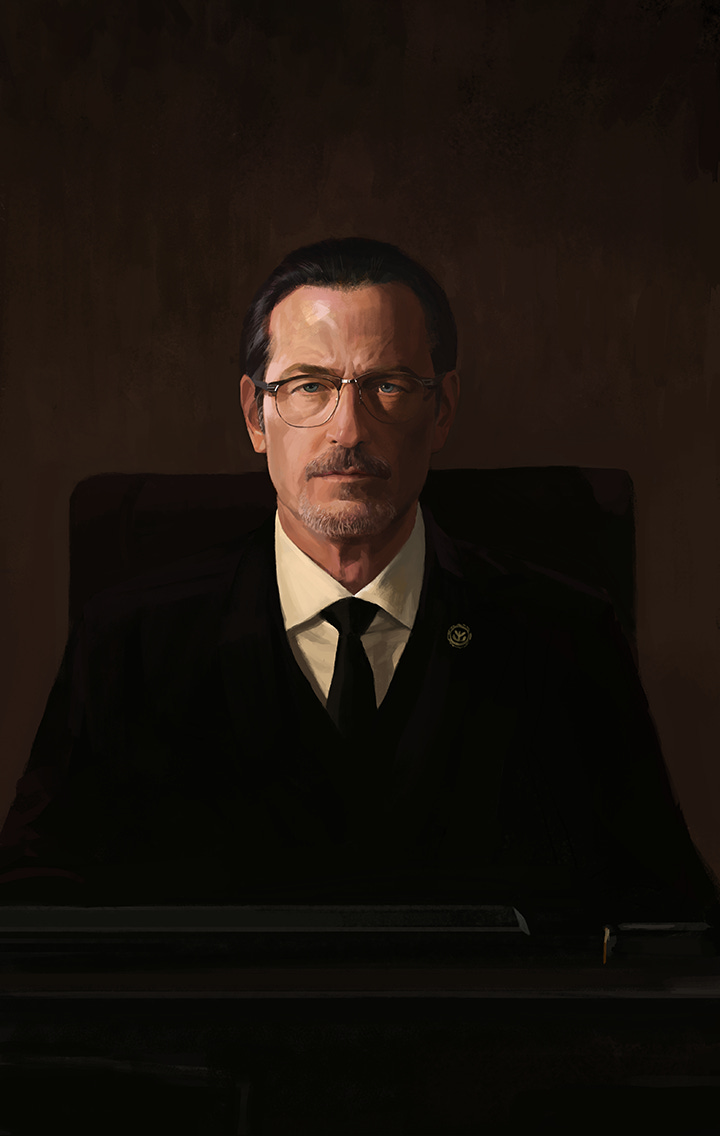

This essay is dedicated to James McCaffrey, the voice and face of CONTROL’s Zachariah Trench. We learned of his recent passing today, leaving us with his incredible performances. Max Payne, Thomas Zane, Alex Casey, Zachariah Trench. CONTROL would not function without him. Every tragedy is the same, every time of death too soon. I hope he finds peace.

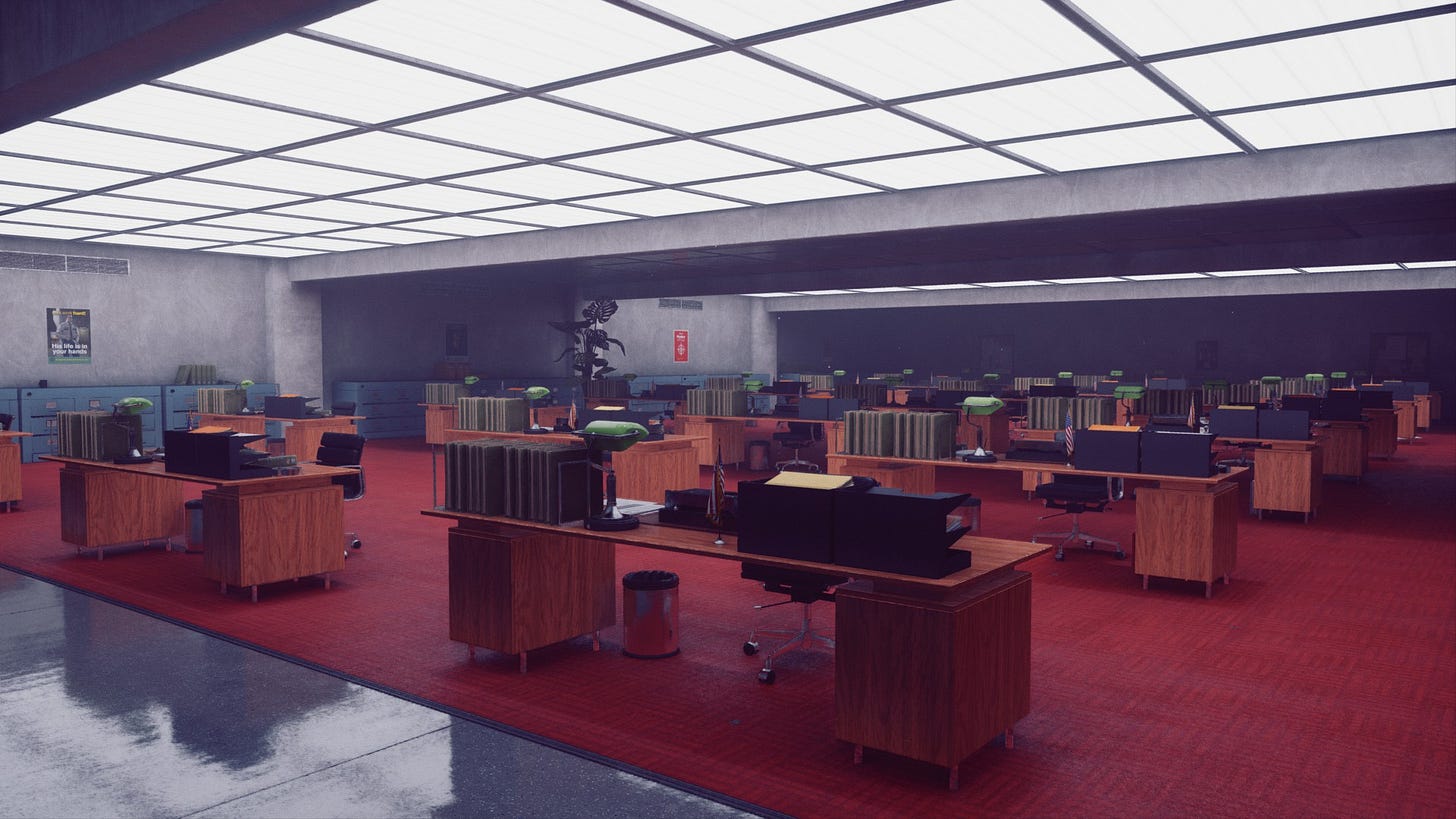

This essay has changed shape almost as much as the Oldest House does. The setting of the video game CONTROL, the Oldest House is a nondescript yet entirely distinct brutalist behemoth in New York, hidden to all but those who wish to find it. It is a building made of solid concrete, yet it frequently rearranges itself beyond the laws of phsyics. It is almost labyrinthine - no, not almost. It is literally labyrinthine, a maze of mysteries and uncanny familiarity. The Oldest House may be a paranatural HQ for the Federal Bureau of Control, a fictive government agency concerned with containing and curbing the paranatural, but its interior frequently looks like any old office building.

While its confounding geometry and shifting corridors are well documented in the game’s discoverable files, there are posters explaining to employees that “DELAYS CAUSED BY HOUSE SHIFTS DO NOT COUNT TOWARDS OVERTIME!”

A mind-numbingly bureaucratic and professional broadcast providing step-by-step information about what to do in the event of “an unanticipated Building Shift,” is broadcast in parts of the building. The Oldest House may be something from beyond or outside of our reality, but its inhabitants have chosen to control it through the languages of capitalism.

The titular “control” of the game, while typically framed in-game as a lens for personal agency, is frequently rhymed with the systems of control that capitalism shackles us with. From propagandization to institutionalization, CONTROL harbors no illusions about the realities that it twists and reshapes. It is hard to know where to begin, whether to follow the timeline the game presents the player, move through the different resonances that the game amplifies, or build a different timeline out of the pieces that it provides. The choice of where to start anything is a necessarily violent and reductive act, as any cursory study of historiography will tell you. We’re going to begin with something ordinary.

Heavy plot spoilers for CONTROL follow! If you can play the game, you should do so! Though please do return to this piece afterwards. If you do not plan to play it or want to play it with my analysis in mind, I do not intend to supplant the experience of playing it. If an analysis of something took away its resonance, then it would fucking suck, something which CONTROL most certainly does not. Enjoy!

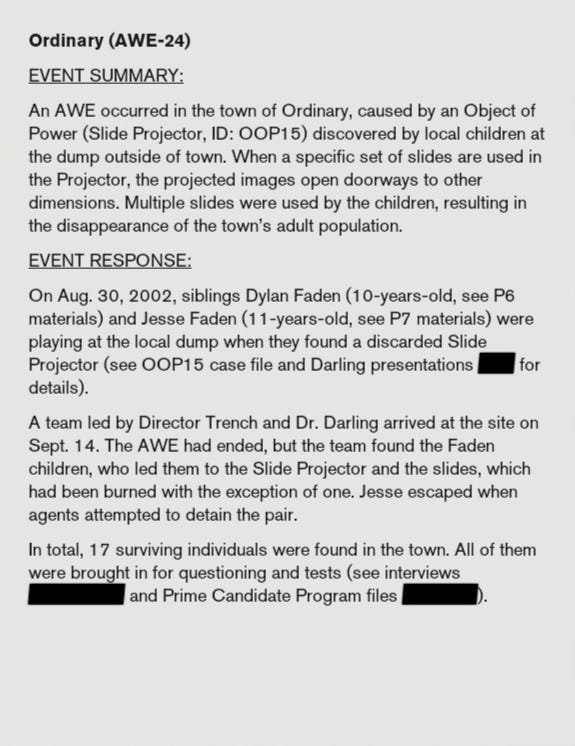

This is how the FBC summarizes the Altered World Event that catalyzes the events of the game:

Jesse Faden is the protagonist and player-character, and it is while looking for answers about the events in Ordinary (a town in Maine! which is likely a Stephen King nod given the adoration for King that permeates another Remedy game, Alan Wake) that she finds the Oldest House. This is where the game begins, with Jesse’s entrance into a nearly empty building that a voice in her head (Polaris, who she met in Ordinary) guided her to. The game begins through Jesse’s eyes, connecting itself to the personal traumas of someone who experienced the Ordinary AWE, not those who cleaned it up and filed it away.

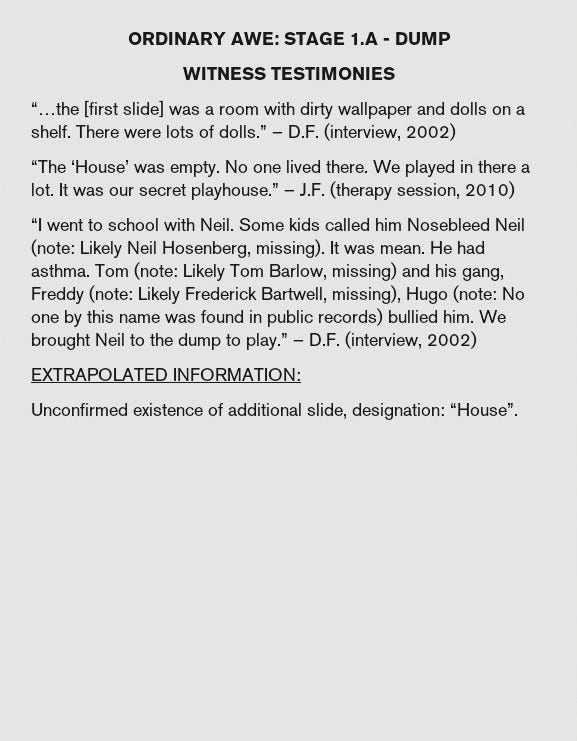

The slide projector was found in a dump, a literal home of the detritus of capitalism (at least the non-human detritus). As Jesse’s psychiatrist says, “A dump is a place for lost things.” The Faden siblings found comfort in a place where other castaways were tossed, and they began exploring the slide projector to play; to escape the frustrations and abuses of the real world.

The trouble truly began when the Fadens brought Neil to the dump, something which they did to help him feel included. Neil was bullied for his asthma, and the Fadens took him in to help him escape. Had any of these kids been shown real love and compassion, instead of punishment and control, these events may have been averted. It is notable that these witness testimonies are peppered with FBC notes about locating and classifying every person mentioned by Dylan. The Federal Bureau of Control is interested in containment, not understanding. This ethos is echoed by the psychiatrist that Jesse meets with a few years after the events in Ordinary. While the FBC successfully abducted Dylan right after the Ordinary AWE, Jesse evaded them, and they are left to grasp at straws of surveillance and recordings to try to keep up with her. Jesse’s psychiatrist asks, “Did you ever feel that way when you were growing up, Jesse?” referring to a feeling of being lost, like the trash thrown into a dump. Jesse is taken aback by the question, but she does admit that she felt some of that, “No… yes, but that has nothing to do–” Jesse rejects the psychiatrist’s attempts to file away her experience as a manifestation of traumas or a wholly imaginative invention. While the kinship between the detritus of the dump and Jesse’s own experience may be true, it does not serve as an answer. To name the connection does not solve the problems that produced Jesse’s alienation or necessitated the creation of a dump. Just as the FBC does not seek to understand, neither does the psychiatrist, asking Jesse unending and inane questions trying to search for a comforting rationalization that will absolve her of the responsibility to the traumatized human that she is supposed to be healing. Jesse refuses to engage with the psychiatrist’s questions, as she can tell that the psychiatrist is trying to find a way to wave away the supernatural events that Jesse knows she experienced. The first time that Jesse refuses to answer, the psychiatrist does not listen and simply repeats a newly phrased version of the same attempt at comfortable classification, “As a child, did you ever fantasize about worlds inside pictures?” This nearly defeats Jesse, as her answer to this second salvo of rationalizations is not refusal but, “I don’t think so, I don’t remember. Maybe. I don’t know,” in a weary and exhausted tone. The world is constantly trying to convince Jesse that what she experienced was not real, and at some point, it becomes easier to believe them and not yourself.

Jesse’s second session with the same psychiatrist goes worse. She opens up about the loss and emptiness that she feels, something which the psychiatrist files away as grief for her dead parents and brother. Jesse (and the player/listener) know that Dylan is not dead. Predictably, a traumatized woman insisting that her brother is not dead, just abducted by a government agency she cannot name and that no one knows exists, is not taken seriously by her psychiatrist. Her psychiatrist tells Jesse, “It is natural for you to feel that way,” a horrifying normalization of the grief and trauma that Jesse carries. It is not natural for your brother to be abducted by a shadowy government agency. It is not natural for the world to deny your experiences and emotions. It cannot be, though we are so often told that it is. This naturalization of horror is exactly what the FBC must do, just as their counterparts in our real world do for the horrors that our government commits.

In this second session, Jesse expresses that Polaris (the guiding voice in her head, a force which the player knows to be “real” in whatever sense matters) is telling her to go to New York, where the player knows that she will find the Oldest House and begin the events of the game. Jesse understandably gets frustrated at her psychiatrist’s continued insistence that Polaris is an “imaginary friend” and what happened in Ordinary was just an “industrial accident”, and it is this animated frustration that prompts her psychiatrist to reveal the true proximity of the connection between the conditions of the two Faden siblings. Dylan is literally imprisoned in a cell in the Oldest House, but the psychiatrist tells Jesse, “you know we can’t let you go until you’re well. And that begins by understanding what’s real and what’s imagined.” The same forces of institutionalization/control shackle both of the Fadens, even as one is nominally free. This truth underscores CONTROL’s broader commentary; just as the FBC’s cover-ups echo the propagandization that real government agencies perform, so too do the institutionalizations of the Faden siblings; into the broader tradition of institutionalization and incarceration as a fix-all for the contradictions of capitalism.

These truths about Jesse’s experience are buried in recordings that can be easily missed by most players, and even if found, easily ignored. Dylan’s incarceration is the key driving force in the game, a completely unmissable characteristic of the world and Jesse’s own journey. The FBC has an entire sector devoted to containment, and a significant portion of the game is spent traversing the Panopticon, a nod to Foucault that seems blissfully unaware of the irony of its construction. The Panopticon is where the FBC keeps all of the “Altered Items” that they retrieve from the outside world. Jesse notes, after fully assuming her role as director of the FBC, that keeping this volume of reality-altering objects in such close proximity is incredibly dangerous. The Panopticon was built by Zachariah Trench, the director before Jesse whose “need for control” (as named by Jesse) created the crisis that Jesse must clean up throughout the game. Trench unleashed the Hiss, the antagonistic force which has hollowed out the Oldest House and nearly crippled the FBC when Jesse arrives. The hubristic failure of Trench’s endeavor to deal with the Hiss bodes poorly for the Panopticon, and Jesse’s explicit naming of Trench’s failure due to his need for control rejects the paradigm of containment and opaqueness that led to the Hiss outbreak. Jesse’s connection to Dylan does a lot of this rejection, as a personal experience with the failures of the Bureau should allow her to lead it better. While Jesse’s stewardship of the Bureau looks to be an improvement, the questions about her leadership are where CONTROL turns away from optimism. It was Trench's desire for control that doomed the Bureau, but Jesse has only taken control, not toppled the status quo.

CONTROL finds some of its most radically resonant content in its suggestions of how to survive in the world of the Oldest House. Where the recordings of Jesse’s therapy sessions indicate an understanding of the flaws/dangers of conventional definitions of insanity, the janitor of the Oldest House, Ahti, demonstrates how insanity can be a map to navigate this twisting and uncertain world. We do not live in an office building that randomly decides to move itself around, but our reality does share the same constancy of inconstancy. When Jesse meets Ahti, his strange Finnish idioms and total surety of why she is there prompts her to say, “I’ve done enough nightshift loner jobs to know it makes us come off weird.” Where Ahti’s strangeness could have been brandished as some scary and bizarre tendency separate from Jesse’s own experience, where he could have been othered as similarly strange people often are, Jesse’s dialogue connects her to him. Ahti is treated an extension of the protagonist and the player; he is treated as a friend. Ahti is the only character other than Jesse who doesn’t desperately try to categorize and classify the bizarre phenomena of the Oldest House. Ahti is also the only person other than Jesse who survives the Hiss outbreak without a Hedron Resonance Amplifier to protect him. Jesse repeatedly mentions that the janitor always has the keys, highlighting Ahti’s profession as one of the things that makes him special and capable of navigating the Oldest House. Every employee of the FBC that Jesse meets has some level of comfortability with the Bureau’s headquarters, but the guns and paperwork that they brandish to try to control it are constantly at odds with the space in a way that Ahti never is. Jesse’s friendship with Ahti is a marked contrast to the frustrations that many FBC staff express towards him:

A janitor who is frequently looked down on and sidelined by the other employees brings a specific class character to CONTROL’s analysis, and Jesse’s success at running the Bureau and dealing with crises while valuing Ahti’s advice indicts the classist superiority complexes that previous FBC employees harbored. To speak more to Ahti’s importance, he frequently calls Jesse his assistant, even once she has fully assumed her role as the Director. Jesse does not push back against this, refusing to adhere to the presumed hierarchy that has been grafted onto a place which itself does not bend to capitalist modes of understanding.

Jesse’s opening monologue reminded me of Morpheus’s words to Neo when they first meet in The Matrix, a resonance that helped me see CONTROL’s own radicalism:

I know exactly what you mean. Let me tell you why you’re here. You’re here because you know something. What you know you can’t explain, but you feel it. You’ve felt it your entire life, that there’s something wrong with the world. You don’t know what it is, but it’s there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad. It is this feeling that has brought you to me.

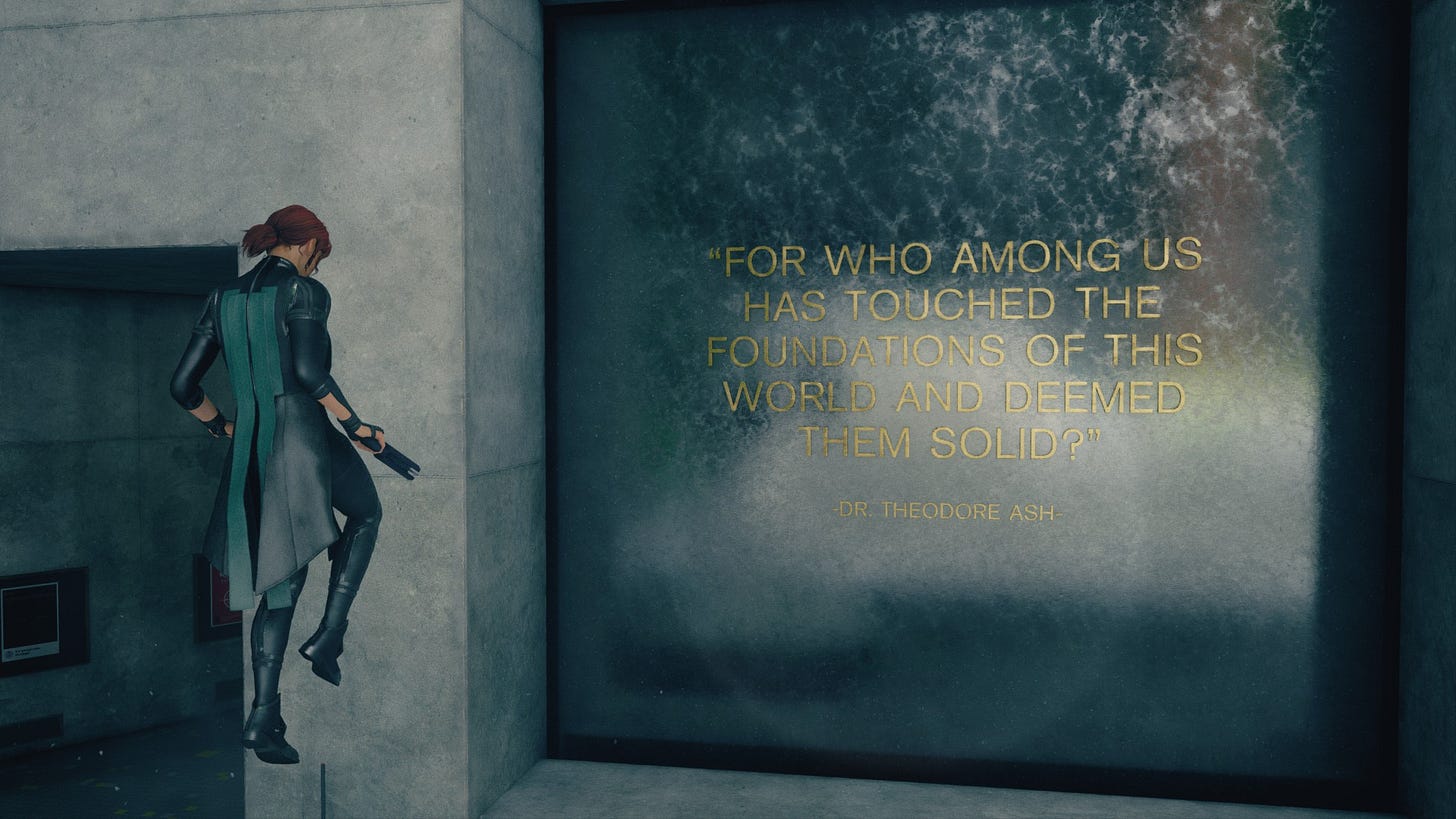

Jesse has always felt off-kilter from the world. Her experience in Ordinary set her at odds with the rest of the world’s understanding of reality, and for 17 years of her life she searched for the Oldest House. When she finally found it, it felt like home. It was where she was always meant to be. While the questions never end, the comfort that you are where you are supposed to be, fighting for what you know is true despite everything that says you are wrong, persists. CONTROL suggest that there is a necessity to insanity, that bureaucratic classification is inadequate for our confounding world, and that the varying levels of evil all stem from the same forces of control dominate our lives.

It is no coincidence that the town is called Ordinary. It is an ordinary occurrence for a town to disappear and yet still stand. There is a recording of the FBC’s astroturfed paranormal radio show where a listener calls in to question the narrative about Ordinary, claiming that the town is still intact and standing empty where a typically populated Maine small town used to be. What the FBC called an industrial accident is more frequently called a bomb, a missile, or a ground offensive. Look at Gaza, north Korea, or Cambodia. Many ordinary towns have been hollowed out, leaving but a few survivors to be swallowed up by the same systems that destroyed them.

In a recent interview with Gene Park, Sam Lake (the lead writer for CONTROL and the auteur figurehead of Remedy Entertainment as a whole) said, “I think we are prisoners of these ideas, and we have such a strong desire to find the answers and make up the answers. We are very, very eager to create rules and laws and define things. In fiction and in art, it’s important to try to break out of that. It might be that we are incapable of fully doing that, but the pursuit is important.” I have yet to play Alan Wake 2, the game that contextualizes much of this interview, but this quote resonated with my own radical reading of CONTROL. The attempts at control that the Bureau is constantly putting forth always fail, but they are indicative of this desire for definition that we have been forced to lean on. When we can lean into the uncertainty, choosing to lean on friends like Ahti or our faith in ourselves like Jesse does, we can begin to build a new reality.

There is so much more to be said. I have hundreds of words of notes that I barely touched on in this essay, but I needed to stop myself somewhere. I could definitely keep going but I’m at the limit of what I want to put into this as an essay - for now. In all likelihood I’ll expand and rewrite this for a video essay or something similar in a few years. I can’t write about everything. One day I’ll try really hard to, but today I’m cutting myself off at 3000 words.

I barely talked about Alan Wake. I barely talked about the nightmare/epilogue that makes much of CONTROL’s anti-capitalism shockingly explicit. I didn’t talk about the poster! I barely talked about Hedron/Polaris. I didn’t talk about self-catalyzation and how Polaris probably isn’t actually a separate entity from Jesse. I didn’t talk about how I’ve played this game twice and both times it felt familiar and like a memory, despite the first time obviously being the first time and having forgotten nearly all of it by my second playthrough. I didn’t even talk about how it’s probably my favorite game! I didn’t get to talk about how I’ve written nearly three thousand words and feel that I have barely scratched the surface. I still need to beat its DLCs too. And then play Alan Wake 2. God. I hope this gave you something. Thank you for reading; thank you for being here.