Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast depicts a near future 2044 where AI has solved climate change, saving humanity from the catastrophe that clouds every corner of our reality. This fictional future is not one of utopic bliss. The streets of Paris are nearly empty, mirroring the emotional condition of its people. Léa Seydoux plays a woman who undergoes a “DNA cleansing” process which is meant to remove all “affect” in order to allow her to perform more fulfilling work. The film follows her through two of the past lives which this process unearths for her. Suffice it to say- the process fails. The “solution” that the AI has cooked up in this speculative reality is… deeply imperfect. Even though some patrons of the surreal club that Léa’s character visits claim that “Nothing can happen to us now, the catastrophe is behind us,” there is plenty of catastrophe in front of them.

For a system that creates so many endings, capitalism is paradoxically obsessed with refusing the finality of those endings. It is not profitable for a story to end. It is not profitable for something to simply stop. There must be growth, there must be more, there must be a tail for the snake to eat, no matter if it is its own.

This is no more true than when discussing the apocalypse. The apocalypse is a frontier. It is an opportunity for growth. It is something to be conquered. It is something that is always in the future. It is always out there, ahead of us, in the same way as the frontier.

The frontier is a core pillar of capitalism. There can be no growth, which is the base essence of the system, without a frontier to grow into. There can be no perpetual, increasing profit without expansion. This does mean that the framework of “frontierism” is infinitely applicable, but there are such specific parallels in popular images and conceptions of apocalypse and popular images of frontiers that I think it provides a rich opportunity for reframing our understanding of both.

What is the frontier?

The most enduring images of the frontier come almost exclusively from the American west and the genocidal conquest of it. The frontier myth, in the US, was predicated on the willful ignorance of the long history of life in the land that white settlers wished to expand into. This refusal to acknowledge anything outside of one’s own narrow conception and imagination stretches both backwards and forwards, with the denial of preexisting histories echoing the denial of different possible futures. One of the elements that makes the frontier myth so compelling and what has ultimately lent it its core place in the American capitalist imaginary is “the notion that this crucible of American identity was temporary and would pass away. Those who have celebrated the frontier have almost always looked backward as they did so, mourning an older, simpler, truer world that is about to disappear, forever.”1 This myth, one that paved the way for future conquest and expansion, was at the same time deeply concerned with the past, already mourning the wild and untamed world that they had invented for themselves to destroy.

The frontier is many things, sometimes scary, sometimes glorious, and always imaginary. The frontier, as in its prototypical example, is built on fiction. The fiction of an empty space to grow into, the fiction of an unspoiled wilderness that is at once inhabited and destroyed as the conquerors embark across its expanse.

What is the apocalypse?

The apocalypse is another eternally imaginary construct, one who is frequently conceived of as a moment, while the actual instances of apocalypse are much more often drawn-out and agonizing, their slow decay straining any idea of “post” apocalypse or even a concrete beginning point of an apocalypse. Does anyone know for sure when Rome began to fall? Is there one singular incontestable start date for climate catastrophe? The climate crisis is so often glossed, in American conversation and pop culture, as an imminent but not-yet-here specter. The evidence of this apocalypse’s present existence is undeniable, its effects literally surrounding us as we fail to think of it as something current. The catastrophe cannot remain a potent omen if it is grounded in the present, so understandings of apocalypse must stay out of reach. The future is where the tidal waves get so big they swallow cities, the future is where the water runs out, the future is where the bombs drop. These things could never happen now, not here, not to us.

The Fallout games (and the TV show) trade enthusiastically in images of apocalypse and frontier, welding the language of the Western to the language of nuclear anxiety to such a degree that this essay begins to feel redundant. What else can I say that Fallout hasn’t surfaced? Walton Goggins’ Ghoul approaches the wasteland in the language of the gunslingers that he played in movies before the apocalypse (one that, conveniently, can be understood as a distinct moment, though it is foolish to begin a telling of the bombs dropping on the day that they do). New Vegas is a cacophony of references to different ways of understanding the West, the Frontier, from the archaic emulation of one of the most prototypical conquerors of frontiers in Caesar’s Legion to the cutthroat business acumen of Mr. House. New Vegas does well to position its three major players as three different forms (frames?) of imperialism, building a triad that effectively reveals far more in their similarities than their differences.

Bodies and Gender

“The mythic frontier individualist was almost always masculine in gender: here, in the wilderness, a man could be a real man, the rugged individual he was meant to be before civilization sapped his energy and threatened his masculinity.”2

The apocalypse is obsessed with images of masculine bodies in violent decay, identifying the societal and environmental decay with that of individual bodies. Zombies are frequently masculine, and though much of this is due to the broader currents of patriarchy and misogyny which inscribe masculine gender markers as the default, there are so many stark contrasts (shared across medium and work) between female and male zombie depictions that they reflect smaller-scale trends within the genre. I think of Left 4 Dead 2, with its monstrous and gigantic masculine boss zombies alongside small and slight feminine bosses. I think of Resident Evil 6, where one boss fight sees you fight a… spider-woman centaur whose boobs are far more of the camera’s focus than the monstrosity seemingly intended by her spider legs. In apocalypse, and I suppose more specifically horror, the feminine is rarely disrupted so much as it is enhanced or exaggerated. The horror that comes from internalized misogyny is deemed a deeper and more effective well than something more responsible. Men get twisted and deformed, while the women are pushed further down some path that is inscribed as core to their feminine existence. In Resident Evil 7, Jack Baker becomes an inhuman monstrosity, while Marguerite maintains a distinctly human element. It is effective, but the bug-mother vibe maintains her femininity as a piece of the horror. Jack’s transformation could be read as a similar expansion of masculine ideal, but the text is still equating femininity with horror in an uncomfortably straightforward way. The best horror exploits these well-worn tropes and flips or remixes or otherwise turns them back into gender critique, but as with much of this space, it is a fine line to walk between perpetuating and critiquing such tropes.

I write of this both to attempt to tease out and articulate my own thoughts on this, but also to highlight the tight webs tying bodies and gender and these “broader” themes together. Mad Max: Fury Road is yet another apocalypse that pulls deeply from the signifiers of classic Westerns, and one that is also deeply concerned with gender politics. The apocalypse, like the frontiers of the mythic West, is a ripe opportunity to deprive women of agency and autonomy.

In The Beast, there is fear.

The Saga of Swamp Thing

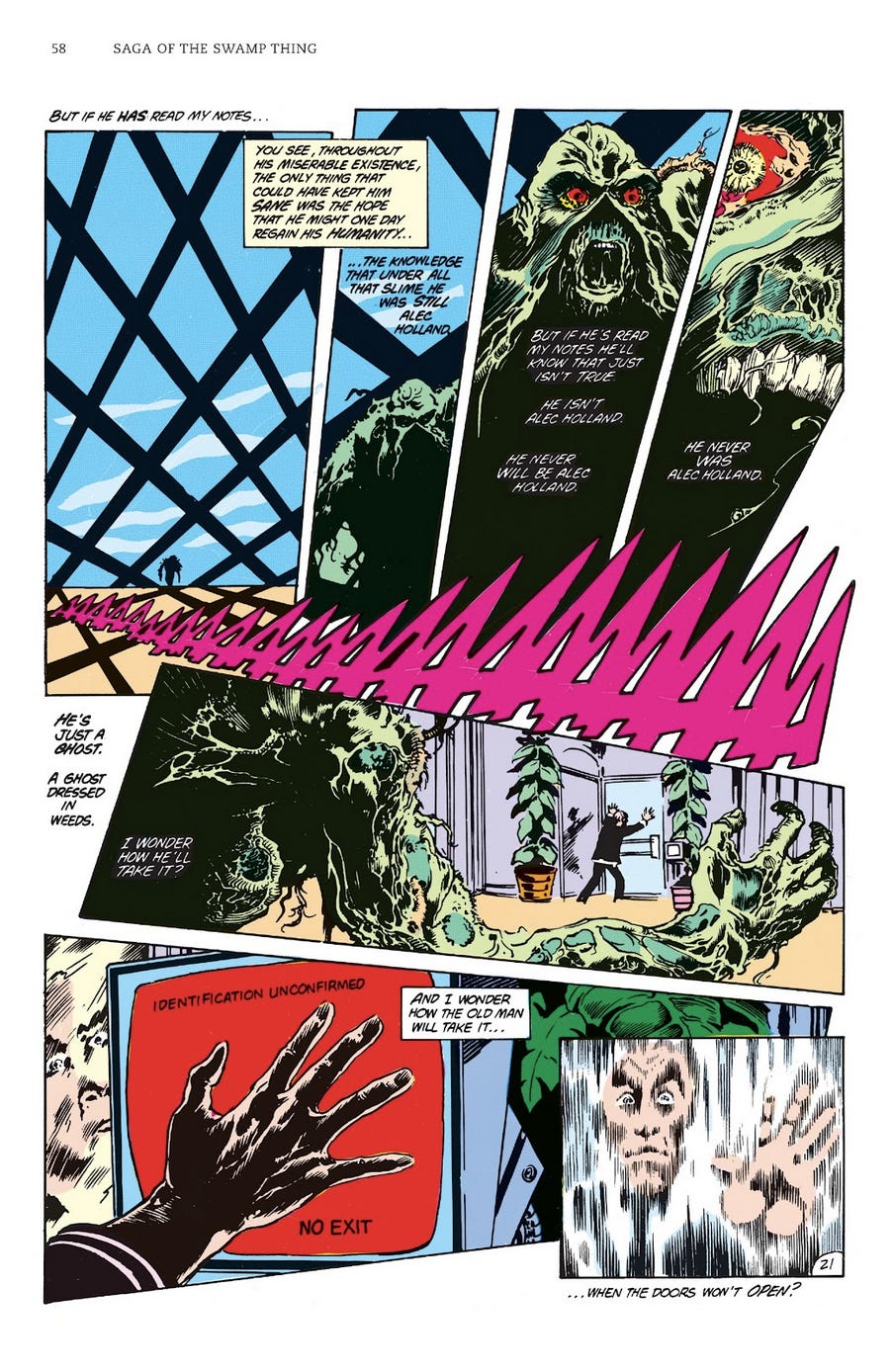

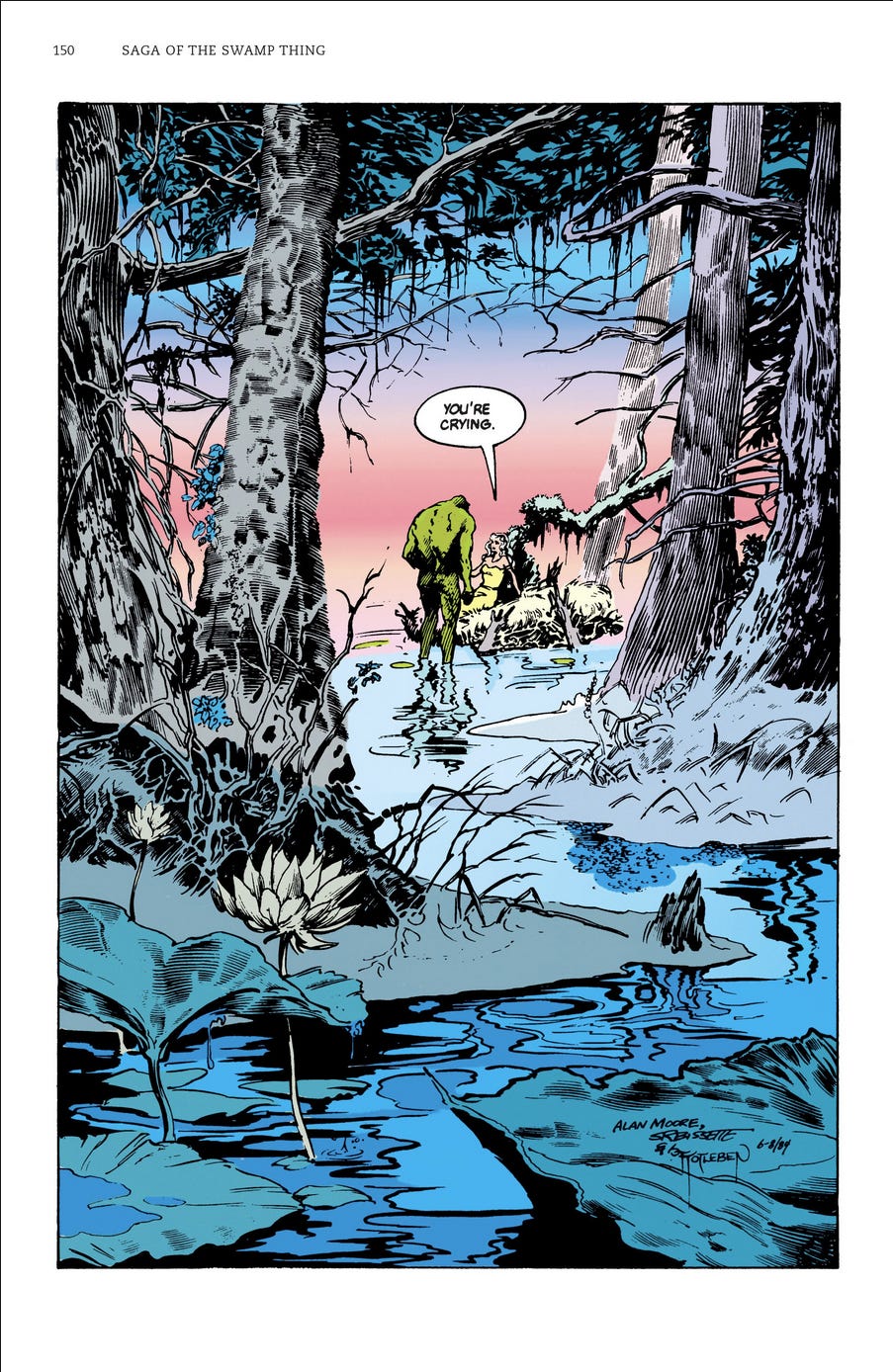

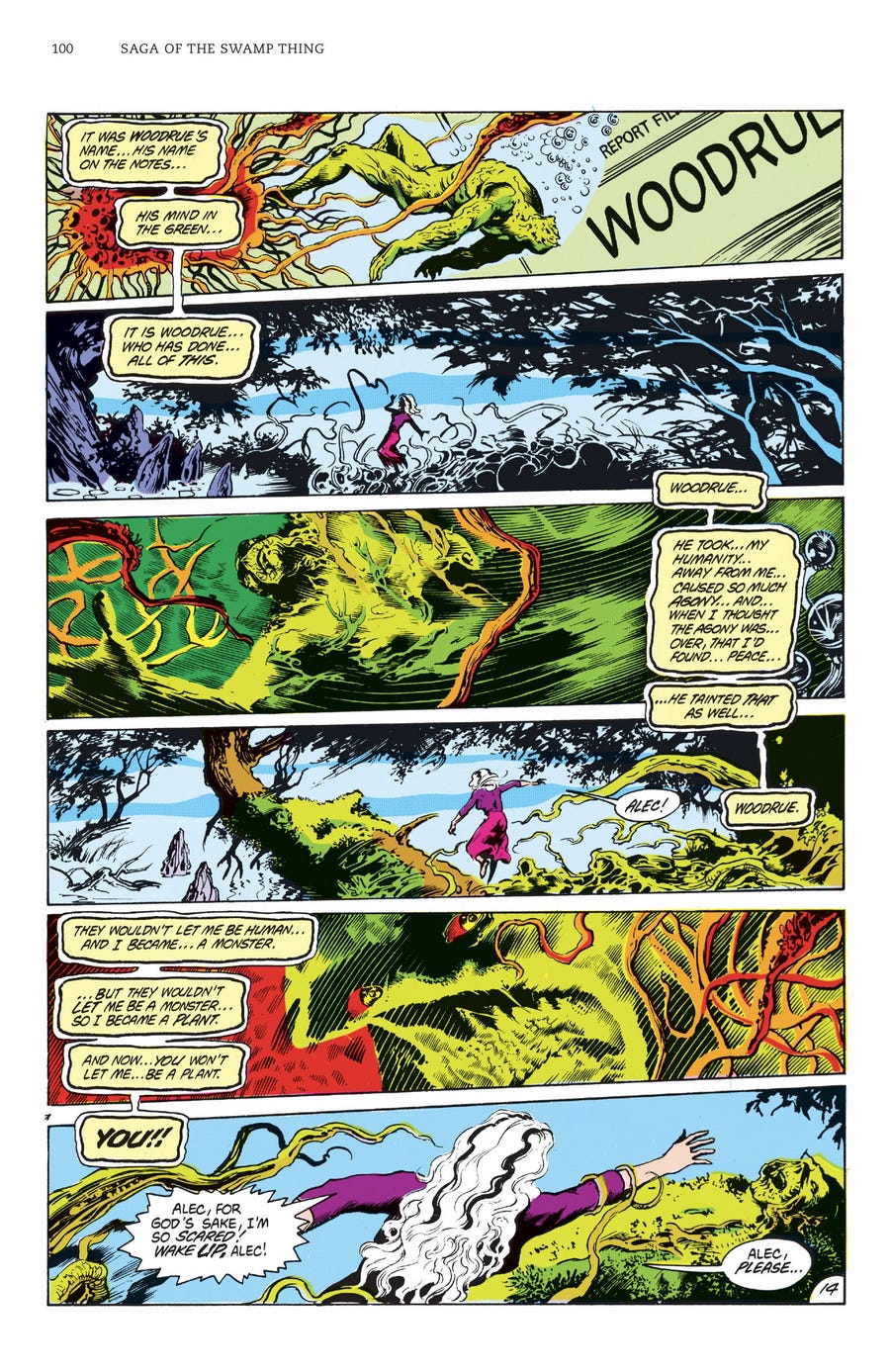

Alan Moore’s seminal revitalization of the Swamp Thing comics3 evokes all of the above-discussed themes with such gusto that it would feel dishonest not to mention it here. Swamp Thing explores bodies and apocalypses in very literal ways with every issue, dancing from questions of what makes him human or not human to grand-scale apocalypse within pages or even panels. Swamp Thing must find balance in his understanding of self, having coalesced from green plant (swamp) matter because a human’s (Alec Holland) violent death in the swamp convinced those plants that they were Holland reincarnated. Alan Moore begins his run with the Swamp Thing realizing that it is not Alec Holland, but this is of course a traumatic realization, and his relationship to this fact remains layered.

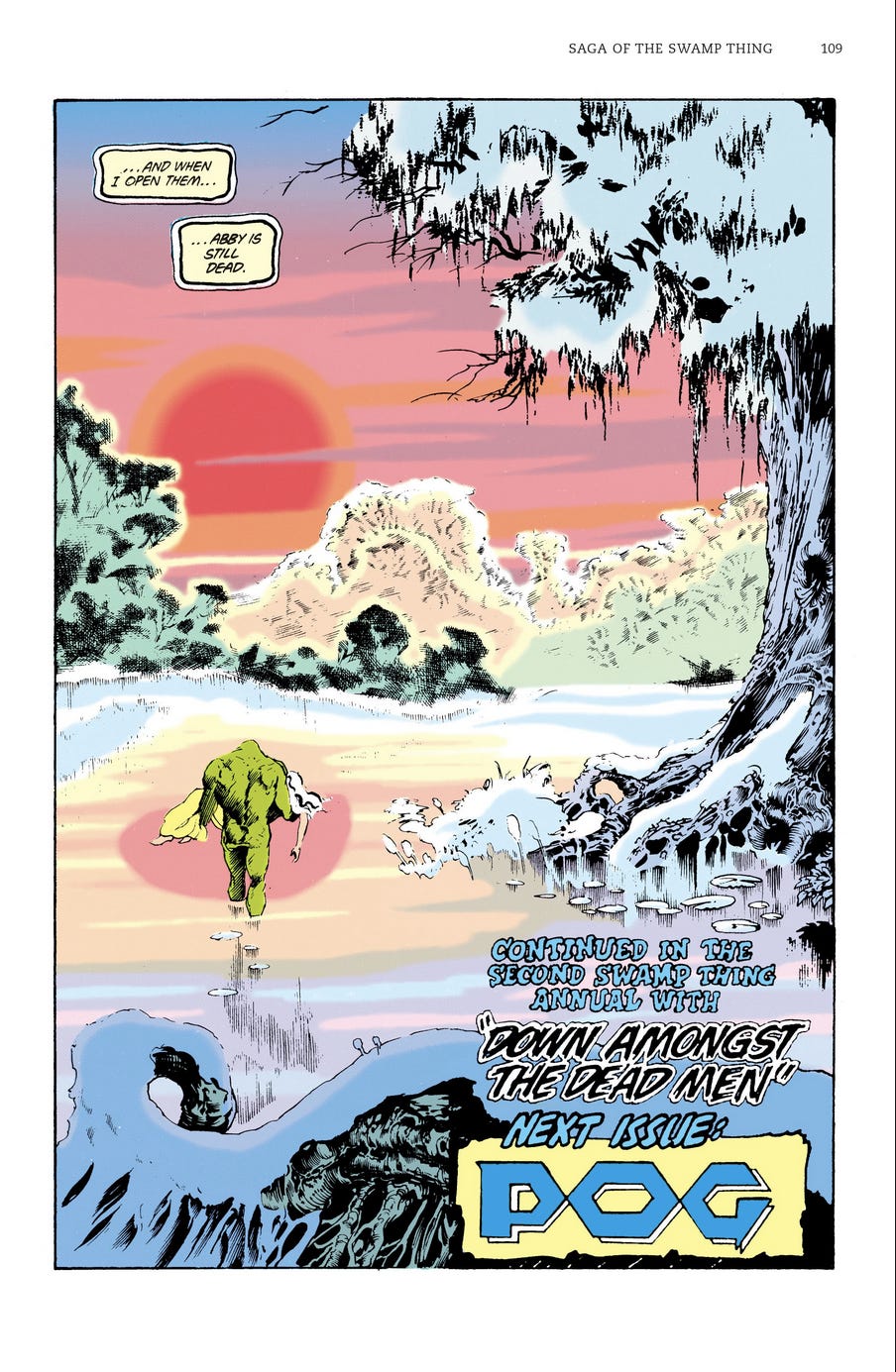

At one point, Swamp Thing must find and bury the bones of Alec Holland in order to allow him to pass into the next plane, a plane which he later visits in the page above. Such a consciously constructed sense of self, one that is so aware of its own flimsy construction yet repeatedly chooses to hold onto the humanity that it knows is a whole-cloth invention, raises questions of the construction of self in much more mundane circumstances than those of Earth elementals and apocalyptic supervillains. What is it that makes a man, what is it that makes a human, and what is it that makes the world we live in?

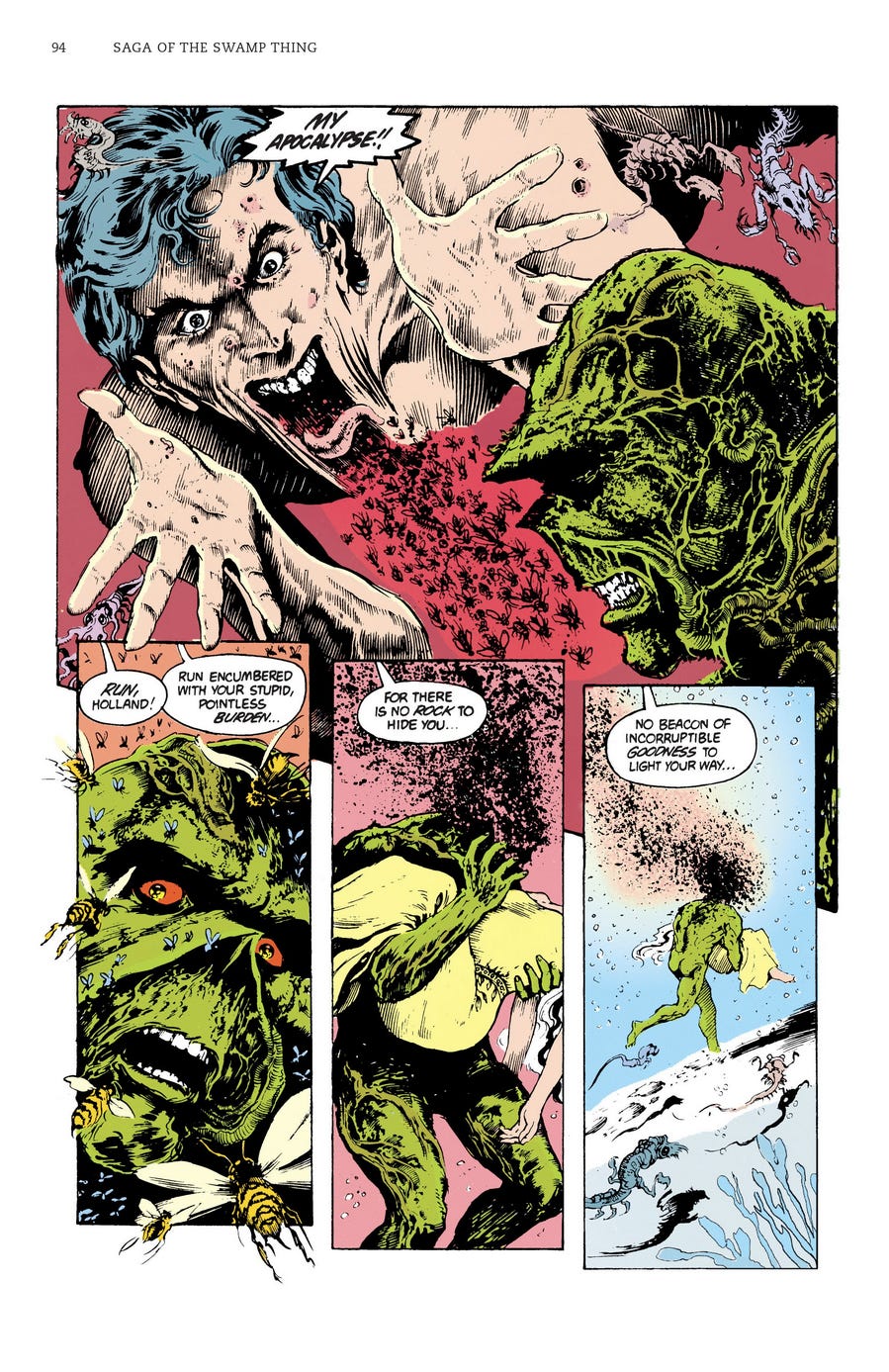

What does The Saga of the Swamp Thing have to say about apocalypses? Its first comes from Dr. Woodrue, who attempts to turn himself into something elemental like the Swamp Thing, but only manages to twist the power of the green to his own masochistic and destructive ends. The second comes from Arcane, who unleashes waves of what amount to bad vibes alongside armies of “recorporated” undead. Arcane claims the ensuing disasters as “[his] apocalypse”:

Such a personal and individualized apocalypse seems to elude the “frontier” label, but this elision does not exempt it from the same dynamics that cloud every other aforementioned example. Arcane occupies the body of one Matt Cable, the husband of Abigail Cable, a man who died in a drunk car accident after a fight with Abby. He agreed to let Arcane occupy his body as his only chance at continued life, a life that had already been forfeit by his disconnect with Abby and… well there’s more but I’m not quite sure I get it I think he had magical powers and didn’t really use them either way he got got by societal pressures and alienation much like any other victim of capitalism.

The Beasts

The Beast’s beasts are mostly abstract, though there are some curious games of gender and pursuit that lend it more of a literal edge. The beast of House of Leaves is much the same, existing only in vivid and visceral visions, never (at least through the first 250 pages) causing direct harm with its own claws. Its presence, imagined or otherwise, certainly causes horrific harm to others, but its claws have not yet dug into the throats that Johnny Truant seems convinced they will.

It is hard to live in a world with such heavy specters. There is always a new horror. Many of these horrors deny the privilege of dismissal, with even the “imagined” ones causing unending harm. Many of the stories I have discussed do not end with the elation of triumphant victory, and I don’t think that our story will either. The victories are smaller, more mundane, and more vital than some single moment of celebration could ever be. I’m not sure how to find our way out of this, but I know one way to start.

We must stop thinking of apocalypses as moments. We must stop thinking of frontiers. We must reject the forward march of some mythic “progress.” Frontiers do not exist, the only march forward must be towards a more just and beautiful world. We must learn how to be. That being must reject the chains that bind the world to injustice, embracing that which makes us human in the chaotic sea of inhumanity. The lakes that we find ourselves in must pool to make an ocean which can drown our oppressors, denying them the profitable apocalyptic frontiers that they are so intent on building.

William Cronon The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature. page 7

Ibid. page 8