“Where could I hide? Where could I hide? I ran in all directions and the sun hurt my eyes.”1

Much like any other knowledge production, this piece came together in parts. I jumped around from words inspired by lectures to words inspired by movies to words inspired by conversations with friends to words inspired by other words to words inspired by organizing. I am beginning to see this as the only real way to write anything. This may be the only way to do anything at all. All processes must be syncretic, and what syncretism is stronger than one that bridges every “separate” realm of life. A great detective uses every kind of evidence they can find, a great artist draws from every part of life they can access. This piece attempts to bridge some of the most persistent thoughts I’ve been carrying lately, drawing on some of the connections that have spun into a barely-parseable web in my mind.

Epistemology is a big word. A big word full of questions. How do we know anything? How do we produce knowledge? How do we know knowledge? How does knowledge production change in different contexts and environments? What can be ontologically known? What can never be known? How do we determine what constitutes knowledge? The questions of epistemology are nearly infinite, and frequently threaten to drive even someone unhealthily obsessed with them into total dissociation.

I want to begin a dive into some of these questions with possibly the most important one:

What is the point of a question?

Many schools of thought claim that questions are meant for answers, that the most important element of a question’s posing is the definite and objective axiom that fills the space after the question mark. This is a convenient paradigm, one where questions and answers can be boxed up and shipped off to other fields and real world applications. There certainly are times when answers must be taken at face value in order to move forward, but the illusion that these answers are truly definite or objective is a falsity, one which bleeds beyond the convenient necessities and often perpetuates real harm.

I think of detective stories, whose explorations of criminal mysteries position them as remarkably insightful artifacts of the history of knowledge production. Many detective stories reinforce a conservative status quo, through rigid categories of knowledge that a detective accesses and a strict social order that is restored in the process of solving a mystery. These examples are often preoccupied with the deviance of the culprits, using the skill set and tropes associated with detectives to reestablish the social order that the criminals disrupted.

Responsible detective stories interrogate the very notions of this social order, often questioning the possibility of democratic and objective knowledge production. Leonardo Padura’s Havana Red is one such example, shining a light on the fallability of the typical detective toolbox, “if we need to invent something to implicate the painter, we will, won’t we?”2 Padura frequently explores the fact that the tools of detective work are not evenly allocated to the actors involved in a crime, something that is often seen as an unquestioned good, but in the messy morality of the detective of Havana Red and the constant fluidity of his evidentiary work, where he is often being interrogated just as much as he is interrogating a suspect, the goodness of such a hierarchy of tools is problematized.

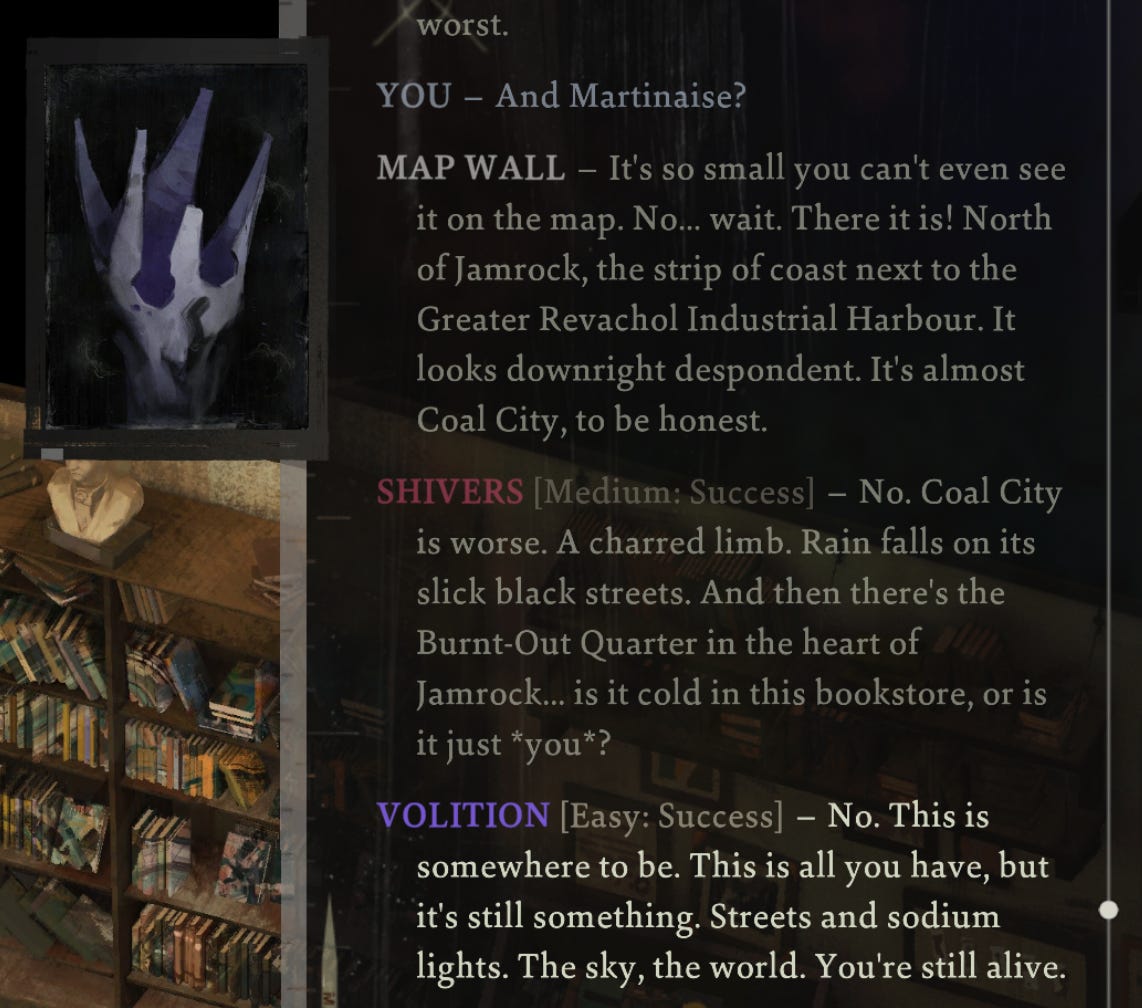

Disco Elysium is another example of a detective story that uses the central crime and the familiar framework to explode outwards into a critical exploration of the systems that engender crime in the first place. While conservative detective stories use the framework of crime solving to reinforce social hierarchies, Disco Elysium takes this same framework and explodes it, raising similar questions to Havana Red with respect to the possibility of “correct” knowledge production. The detectives of both of these stories are deeply unreliable and flawed, a fact that in itself challenges the allocation of crime solving tools. A line of questions necessarily follows this reality:

Why should a drunk misogynist be granted the authority to carry out interrogations and evidence collection?

Who decided that this person should have authority?

Where and how does this authority originate?

What is the purpose of this authority?

I do not have time to delve into these questions, but the fact of their raising is what makes stories like Disco Elysium and Havana Red vital to rewriting our understanding of epistemology. Disco Elysium further problematizes the constructions of power, authority, and social order through its setting’s resistance to the very presence of the police, their authority often proving thin and limited in a space that is ruled by different forces.

Crime “solving” is itself a deeply problematic framework, perpetuating a conception that implies an objective solution can be reached. This is the central idea that I want to challenge here, and I bring in these deconstructions of detective stories to illuminate the fallacy of objectivity and the very concept of “answers”. In Havana Red, Detective Conde learns far more about the world in the process of his investigation than from the identification of the culprit. Try to think of the last time an answer to a question taught you more than the journey you took to arrive at it.

Who gets to be known?

This is another of those eternally unanswerable questions. This is a question that nearly all of my classes right now are engaged with, from studying metageographies of the Caribbean to unpacking categorizations in British colonial India. The erasure of groups that disrupt and threaten Imperial social order is a well-documented phenomenon, primarily through the almost anti-documentation that occurs with respect to these groups. In her book Creole Archipelago, Tessa Murphy discusses one example of this, “Despite the absence or erasure of Indigenous people from many of the documents authored by Europeans, closer reading of these colonial texts reveals that the Caribbean’s Indigenous inhabitants continued to exercise diplomatic and military power long after they were supposedly exterminated, expelled, or enslaved.”3 Murphy’s negatively constructed research is not dissimilar to the construction of detective stories, where the void of a dead body can be reconstructed by their newfound unpresence in the lives they were woven with.

The histories of who is allowed to be known, seen, and studied has had a big year at the movies. Three of the year’s most talked-about movies (in the interests of disempowering the Academy Awards, I emphasize that fact and not their shared Oscar nominations, but the Academy did legitimize them as significant works of cinema in 20234), Oppenheimer, Killers of the Flower Moon, and The Zone of Interest, are all movies whose storytelling choices demonstrate different approaches to history. These three movies centered around genocides make vastly different choices specifically with respect to the visibility of the victims of these horrors, choices that reflect different strains of historiography and raise further questions about epistemology.

While Oppenheimer is inevitably and necessarily in the shadow of the genocidal results of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s creation, the film never really shows these results. There are visions of destruction and horror, but they are entirely filtered through Oppenheimer’s own limited perspective, a historiographic choice that calls into question the ideas I raised above. There is certainly a question of what a bunch of white men from the US and the UK could have to add to depictions of suffering wrought by the US, whether any ethical depiction could have been achieved, but that should not be used to dismiss this line of thinking, and instead it should prompt us to begin to question the ethicality of the project as a whole. When we tell histories of genocides through their architects, we are engaging in a level of erasure and invisibilization that Oppenheimer only lightly challenges. Oppenheimer is part of a historical tradition of telling stories that actively sideline the perspectives of victims and oppressed peoples, a tradition that should really only exist alongside a true decolonial project that raises the stories of the oppressed and invibilized to far beyond the stories of their oppressors. Once that disparity has been rectified a million times over, then maybe we can begin to engage with the stories of these murderers once again.

The Zone of Interest also chooses not to depict the victims of its primary subjects’ genocide. Nearly every character who speaks in The Zone of Interest is a Nazi, and most of them are intimately involved in the bureaucratic horror of the Holocaust. Despite this visual and narrative emphasis, the victims are still constantly present, whether in the nightmarish sound design or the barbed wire walls that surround the home of the (protagonist?) Auschwitz commandant’s family. One of Zone’s most fascinating choices is the use of thermal photography for scenes of a young girl’s acts of resistance. At night, this girl travels around the outskirts of Auschwitz and places fruits, presumably to nourish and help those who will be forced to work and march through the places she frequents. The visual inversion of thermal photography situates the “normal” photography as an accomplice to genocide, while arguing for a necessity of a new language for resistance. Oppenheimer both refuses/fails to really imagine new languages and allows focuses almost entirely on the humanity of its genocide architects. Zone refuses to allow the Nazis it depicts to be humans.5

Part of why Zone functions effectively while Oppenheimer’s choices come up so short is the ubiquity of Holocaust imagery. There are countless “popular” depictions of the Holocaust, so much so that a distinct visual language has developed around it, propelled by films like Schindler’s List6 (among many many others), that Glazer’s Zone exists in explicit conversation with the choices that those films have made through history. As Glazer situates film itself as a tool of genocide, he critiques such depictions. Oppenheimer does not have a similar landscape. The most popular images relating to the nuclear holocausts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are those of a giant radioactive lizard. This is not to take away of the power of such images, especially those created by those targeted by such horrors — here is another significant piece in this conversation: Jonathan Glazer is Jewish, while Christopher Nolan is, shockingly, not Japanese — but simply to situate the utter irresponsibility of Oppenheimer as an artistic project. There is no signficant cultural counterweight to Oppenheimer’s choices as there is with Zone. Godzilla has been so far removed from his initial context that he cannot be considered in relation to Oppenheimer in the same way that Schindler’s List and the opening of 2000’s X-Men can be for The Zone of Interest.

Killers of the Flower Moon ends up finding a similar conclusion to The Zone of Interest, a resonance that stretches across their rather dissimilar approaches to their storytelling. KOTFM is filled with Osage faces, its cast populated with indigenous actors, a marked contrast to both aforementioned films. Scorsese almost completely rewrote the script when he began consulting the modern Osage Nation, reframing the story to fit with the current understandings that have persisted in the affected community. Yet despite the close involvement of the Osage, the presence of indigenous performers, and the unflinching understanding of the deep evil of the white settlers in the story, Scorsese still ends the movie with a statement on the complicity of the telling in the tragedy itself. I do not wish to spoil specifics here, largely because they could never do it justice, but the final scene of Killers of the Flower Moon specifically implicates the commodification and commercialization of the story of the tragedy in the tragedy itself. This understanding of image-making as a consummate element of history’s horrors is shared across KOTFM and The Zone of Interest, even as their approaches to the depiction itself differ. Oppenheimer contains no such understanding of its complicity in the horrors it doesn’t depict, and even if such an understanding could be gleaned from between its frames, it does not foreground it like Killers of the Flower Moon or The Zone of Interest do.

What can be carried forward?

Jonathan Glazer was the only person at the Oscars who mentioned Gaza.7 Swann Arlaud and Milo Machado-Graner wore pins of the Palestinian flag,8 a welcome contrast to the mystifying “Artists4Ceasfire” pins, but no other winner so much as gestured at the unimaginable tragedy unfolding as Hollywood spent the night engaged in nauseating autofellatio. Glazer’s words rejected the ahistorical separations constructed between historical tragedies, connecting his radical filmmaking choices to the acts of resistance that we must commit to to survive these horrors. In Glazer’s words, “How do we resist? Alexandra Bystron Kolodziecjczyk, the girl who glows in the film, as she did in life, chose to. I dedicate this to her memory and her resistance.”

The illusion of objectivity perpetuated by irresponsible detective stories is borne of the same lie that allows Oppenheimer to refuse to engage with a key piece of its own story, a lie that knowledge can be boxed up and doled out, with knowledge of the architects of a genocide taught in a different classroom than the lesson on their victims, and one genocide discussed without acknowledging a current one.

History must be brought off of the shelf, dusted off, and incorporated into every breath we take, “The city, however, does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand, written in the corners of the streets, the gratings of the windows, the banisters of the steps, the antennae of the lightning rods, the poles of the flags, every segment marked in turn with scratches, indentations, scrolls.”9 We must comprehend the untellings that surround us, bringing the uneven allocations of history — of knowledge itself — into the light.

We must refuse to allow these disconnections and falsities to remain housed comfortably in our minds. We must reconnect with the ghosts that haunt us in every waking moment, forcing ourselves to historicize the paradigms we flit between. In Taylor M. Moore’s beautiful words:

“We are all haunted by specters in our work, and by the stories that pester and eat away at us until they are told. In taking on the mantle of the historian, we all are forced to become mediums, to act as diviners. We all traverse and translate between the worlds that we study and the world in which we live. It is only in embracing the inner medium in us all that we can imagine new possibilities for the history of science and new narrative forms for writing history. And there is still much ground to cover. For, as N. K. Jemisin reminds us, ’much of history is unwritten. Remember this.’”10

I do not ask you to be historians, but I would like you to ponder: What part of life is not history? To understand anything is an act of historicization, and if we continue to be ruled by the same violent epistemologies and historiographies we will fail to channel the spirits that deserve to be divined.

Condé, Maryse, and Richard Philcox. Crossing the Mangrove. 1st Anchor Books ed. Anchor Books/Doubleday, 1995. 204.

Padura, Leonardo, and Peter R. Bush. Havana Red. Bitter Lemon Press, 2005. 86.

Murphy, Tessa. The Creole Archipelago: Race and Borders in the Colonial Caribbean. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1f45qgs, 46-47.

I will save my thoughts on how Mission: Impossible 7 is more radical and historiographically responsible than Oppenheimer for another blog

In this interview, Sandra Huller said that the director, Jonathan Glazer, encouraged her and the other actors to empty their performances of anything human.

Michael Haneke’s comments in this THR roundtable are relevant here, and this video also contains some of the most unfortunate and amusing sequence of interviewees ever — why is John Krasinski answering this shit dude

Calvino, Italo, and William Weaver. Invisible Cities. Harcourt, 1974. 11.

Moore, Taylor M. 2023. “An (Un)Natural History: Tracing the Magical Rhinoceros Horn in Egypt.” ISIS 114 (3): 469–89. doi:10.1086/726113. If you’d like to read this please let me know it’s so beautiful I adore this article!